Ben Davis - Light & Shade

Whether you prefer your cinematic sustenance served via the Marvel Universe or the black comedies of Martin McDonagh, it's likely the cinematography of Ben Davis has shaped your viewing pleasure.

Interview Katie Baron

Photography Perry Curties

We first talk at the annual British Society of Cinematographers expo in Battersea, South London following Davis’s Q&A (for a rapt audience of 200) about his work on Martin McDonagh’s multi-award-winning The Banshees of Inisherin. It’s a clear winter’s day of sunshine, blue skies and monster (grip) trucks in the car park with the kind of million-pound modifications essential for transforming the scrappy contours of real life into epic on-screen tales. Inside, there’s kit, cameras and lenses for navigating every subtle shift in the weather, light or mood; a cine-voyeurs superstore. All of it represents Davis, in technical terms at least, who is famous, amongst other things, for fuelling opposing ends of the cinematic spectrum – both the “popcorn” blockbusters of Dr. Strange, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Guardians of the Galaxy, Eternals, Kick-Ass and Kraven the Hunter (coming October 2023) and the feted, soulful, frequently sad storytelling of Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, Seven Psychopaths and the aforementioned ‘Banshees’. Plus, projects including Tim Burton’s lavish live-action Dumbo and John Madden’s The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. No job too big or too indie.

The glue that binds is Davis’s appetite and talent for spotlighting the truth of the human condition within the meticulous, easily overwhelming business of world-building: “Getting to design worlds [for Marvel] and considering everything from what a toothbrush looks like to where a light source would come from on a fictional planet is incredible, but what I hook into most deeply with any film is the characters themselves and their personal narratives. It’s why I like origins stories so much.” He cites the scene in Dr. Strange where Benedict Cumberbatch in the megalomaniacal title role awakes in hospital to discover his peerless surgeon’s hands incurably mangled: “The shots are constructed to be almost too close to his face, so the audience feels the prevailing sense of discomfort to the point of almost wanting to escape; but not quite.” The same palpable unease appears in ‘Banshees’, an eerie breakup movie of sorts, which is set on a small island off Ireland’s west coast during the 1920’s. Sat in a confessional, Brendon Gleeson’s character Colm displays a first flicker of contrition: “At points we move in so close that you can see his deepest despair, showing the pain connected to this late-life crisis he’s entrenched in. Not fully showing the eyes, just the side of the face, can also be hugely emotional.”

Sometimes, less is so much more. He describes a lakeside scene, also in ‘Banshees’, between the characters Dominic and Siobhán where cross-shooting (where both actors’ faces are shot direct on, in order to alternate between each in the editing process) was the devastatingly simple photographic direction. He recalls it as a point of such raw tenderness and pathos (it presages of one of the film’s saddest sub-narratives), “that it exemplifies why I make movies. It was the last day of shooting, which is always a strange mix of triumph and sadness on any film, and it was just this very special moment to witness.”

Davis’s own narrative makes for an interesting discussion, especially amidst the current furore about ‘nepo babies’. His father, Mike Davis, was also a cinematographer and camera operator and while having a photo lab in the attic is hardly par for most peoples’ course, it was far from a gilded highway to Hollywood. He grew up in Ladbroke Grove, west London, “in a very bohemian house of artists, writers and creatives where heated debate was really important, the kind of cultural discussion that so often isn’t tolerated now in the time of social media,” but also describes his childhood as, “a bit of a mess”. A talented skateboarder (he was sponsored as a teen), he would get dressed in his school uniform and then change downstairs, at one stage bunking off for three months straight until the discovery of forged letters sparked a formal expulsion. “Then there was punk rock, girls, smoking drugs… it was a difficult time.” From age 15, he worked on building sites and as a painter and decorator, briefly travelling to the US to work as trainee on a film with his father. At 19, he returned to “acquire some qualifications; I was ready to learn” and managed to get a job at the National Film School as a clapper loader. After working with several legendary directors of photography including Billy Williams, Doug Slocombe, Roger Deakins and Harvey Harrison, he moved into commercials – just when UK advertising was at the peak of its creative prestige – cementing his love for the art of lighting. “Film genuinely saved me. Of course, my dad’s support helped to get me an interview, but I did the rest and the graft was very real. From then on, I was always learning and shooting; I’d work on anything I could, regardless of budget.”

His first feature film was Miranda (2002), followed by the better-known Layer Cake (2003) directed by Matthew Vaughan and featuring a pre–Bond Daniel Craig. But it’s McDonagh that is Davis’s most notable repeat collaborator, a director for whom he clearly feels enormous personal and professional affection (“despite the dark material, Martin is very charming and affable and he always wants his sets to be places of joy and creativity – it’s not what people necessarily expect”) and who consistently sparks creative gold. He describes how on ‘Banshees’, he, McDonagh, production designer Mark Tildesley and costume creator Eimer Ní Mhaoldomhnaigh would each bring their visual references to the table to create what sounds like a cinephiles dream. In the end, says Davis, “it was a sort of bible of our collective thinking”, the result of a hive mind’s reciprocal influencing.

Westerns were a major theme, perhaps unsurprisingly; it’s not the first of McDonagh’s films to be called a gothic revenge western – ‘Three Billboards’ similarly marries the vast open spaces of classic cowboy movies with the macabre overtones of gothic art. Charles Laughton’s moody The Night of the Hunter (1955) (“Martin has a thing for this film, particularly the animals”), Walter Hill’s The Long Riders (1980) and John Ford’s story of suffering and survival The Searchers (1965) all feed heavily into the adversarial vibe. Gleeson’s character relentlessly strides across hills or up dirt tracks trailing a long black wool overcoat and hat with an oversized crown, in contrast to opposite number Colin Farrell’s put-upon (until a point) Pádraic who is clothed in comparatively boyish caps and knitwear. It’s a masterclass in how visual direction – the 360 manipulation of atmospherics – demands full creative synergy. The process also meant scouting other films with lighting from oil lamps and candles (Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon included), as well as introducing paintings by the Dutch Masters to illustrate the power of glossy dark interiors lit by a single flame, with clustered people often looked in on. “We wanted to emphasise the claustrophobic nature of the social settings, the pubs and houses, which is also why it was so important to have those sweeping landscape shots – they temper but also accentuate the insular psychology of island life.”

Colour also differentiates those forever confined to island life from those whom McDonagh affords an escape hatch, namely the worldlier sister Siobhán. A key reference was the iconic book of Nostalgic Ireland postcards from the John Hinde Archive; a tongue-in-cheek nod to the clichés of rural island idylls in super-saturated colourways, it riffs on McDonagh’s love of blending grotesquely black storylines with the curveballs of slightly daft humour. Siobhán’s red coat is the first hint she’s destined for life elsewhere; the later appearance of another in yellow confirms she’s definitely off.

While Davis is emphatic that the director is always commander-in-chief (when working with other directors, he often brings a selection of 30 images to see what they respond to), there are times when the cinematographer’s viewpoint influences directorial decisions. He describes a moment in the filming of ‘Three Billboards’ where Mildred Hayes, played by Frances McDormand, is putting flowers in a pot below when she’s startled by a beautiful fawn in the field beyond and begins talking to it about her murdered daughter. “It was scripted to be shot at twilight but there was some anxiety about that because it leaves a small window of time to do an extremely emotional scene, which can be especially hard late in the day. But I pushed for the timing and that twilight focus is now a reference point in other films – including ‘Banshees’ – to signal a moment of deep despondency (see Pádraic’s despair at the death of his beloved donkey).” Sad films bring challenging emotions and, notably, it’s not only the actors for whom the work can take a mental toll: “I think people often don’t realise how the entire crew have an emotional stake in the movie and how immersive the experience can be. ‘Banshees’ really took it out of me by the last two weeks. The fact that we largely shot it in chronological order meant that the sense of devastation kept building.”

What films or scenes (not of his making) does he feel represent cinematographic excellence? In Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) he cites both the night robbery at the beginning of the film and the scene where, when photographing the deceased James, a close-up of the camera lens shows the prostrate body inverted (“so brilliant, because you’re never really aware of the artifice”), while in Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather II (1974) it’s the scene where Robert de Niro’s Vito Corleone is seen running across the rooftops of Little Italy, New York before murdering the dandified Don Fanucci amid the feast of San Rocco that gets his eyes flashing (“it’s just so beautifully constructed; I think it’s perfection”). He also flags a sublime montage in Mike Nichols’s The Graduate (1967) which seamlessly segues between Dustin Hoffman’s disillusioned student Benjamin Braddock at home with his parents and in a hotel room with lover Mrs Robinson, played by Anne Bancroft (“I get so much more joy from a perfectly sequenced series of scenes; I really appreciate that skill”) and Woody Allen’s infamous film ode to the travails of dating in Manhattan (1979) for its confounding of visual expectations – unusually for a comedy, its shot completely in black and white and some scenes feature characters talking to others out of shot, or silhouetted way back, shrouded in the depths of the frame.

A cinematographer for many moods, what does Davis prize the most? “Good art should be about ambiguity and I never want to feel like I’m being over-manipulated. You should never see the cinematography, only feel its impact.”

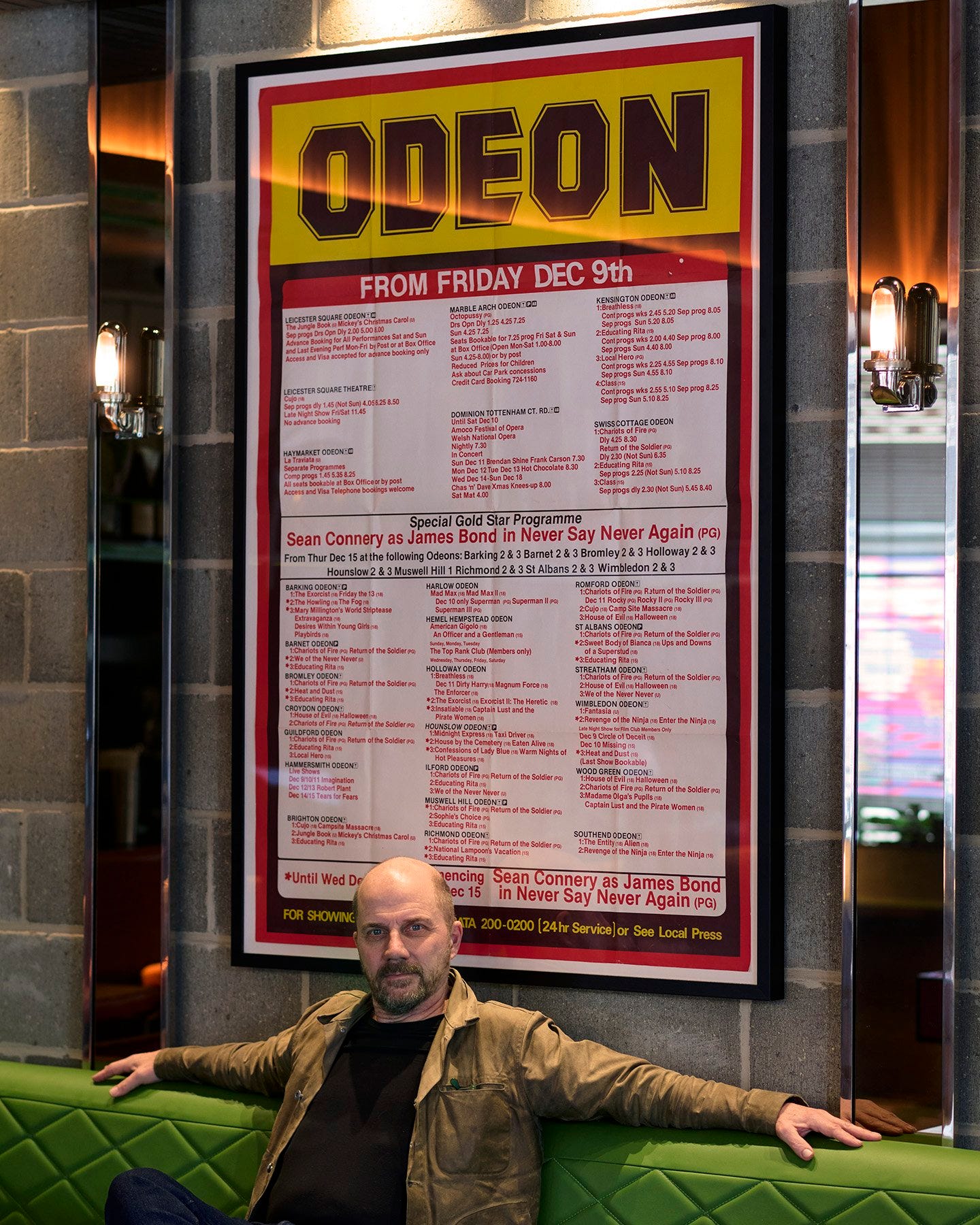

Shot at the Everyman Cinema,

Egham, Surrey